Ernabella Station

© Janet Lane 2024. Image: Ernabella station homestead, Territory Stories.

Ernabella in the Musgrave Ranges, was named by John Carruthers who did extensive surveying and exploring there in the 1880’s. He was based there for four years doing trigonometric surveys for government. Before him, exploring there had been done by the legendary Ernest Giles in 1873, fortunately in a good year for rain, Giles’ 24 horses didn’t go thirsty or hungry. He praised the area highly.

Ernabella was an Aboriginal man who lived there and who was very helpful to Carruthers during his time there, and who also acted as a guide, so he named the permanent waterhole after him. Carruthers thought it would make a good mission station and went 200 miles to buy 13 cattle which he put there to help the people make a living. He also surveyed the state line. At the time Carruthers used camels, but after leaving Ernabella they succumbed to weed poison so he replaced them with packhorses, and returned to Ernabella with the riding and packhorses, some of which made their own way there as his horse tailer wasn’t up to the job and some strayed. He loved Ernabella so much he asked for his ashes to be scattered there when he died, this was done after he died in Adelaide, aged 92, in 1940.

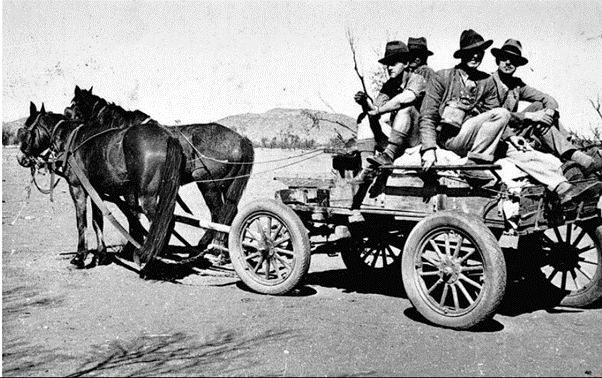

Ernabella was a set up as mission station in 1936. Purchased by the Presbyterian Church from the government for 10,000 pounds – funded primarily by subscription fund raising and with a 1,000 pound government grant. They relied on horses and camels for transport although a motor came along too. When the government Aboriginal Protector T. Strehlow stayed there soon after, he said the local Aboriginals were excellent stockmen, as well could track horses easily in wild country so they could be mustered, and brought back horses and cattle when they’d strayed to neighbouring stations.

Rev. J. Love was first in charge there – the mission was 500 square miles – he used a camel buggy to survey boundaries with the Balfours. He got there by train to Oodnadatta then motor car across to Ernabella, about 270 miles – 434 km’s.

Ernabella thus remained with the indigenous people although run by the church, and was conjoined to 65,700 square miles reserved by the government for the indigenous people there – being the Great Victoria Desert. They were taught to read and write their own language as well as English.

The ministers helped the local indigenous people with food, a school and medical issues, and to run sheep and horses for funds. 2,000 sheep were taken there and a good lot of horses when the mission was set up, can’t find where from.

In spring 1938 – Rev. H. Taylor the superintendent then – with workers ran in 1,600 sheep for shearing and they broke 20 horses in. Some later in 1949, Reverend Love’s wife – they were stationed there again that year – loved riding and used the station horses. The mission was set up to retain some land for the people there, to exclude whites, and to help the people make a living, primarily from pastoral work, and tend to their medical needs.

Horses had been taken there from nearby stations, strayed there from those stations, and some were there from usual causes being strays or abandoned horses from various explorers, hopeful miners, drovers, telegraph line parties on the Stuart Highway to the east and stock routes. Doggers went through the area often as there were water points, at times they too left or had a horse stray. Some came from W.A. area, some from the N.T., some via Oodnadatta – doggers were paid by presenting the scalps to a police station.

Rail had gone through to Oodnadatta in 1891. Several pastoralists had taken up land in the greater area because of the Overland Telegraph line going in, and the railway being built. Many bred horses for the trade, good horsemen such as Bagot. Horses were droved to Oodnadatta, often from a considerable way off, and railed south for the sales. Most went to India.