Breeds Used to Create the Waler

© Janet Lane, based on many years of research which has appeared in various iterations over this time. Image: The Pastoralists’ Review 15th July 1907.

A summary by Janet Lane

An understanding of horse history is key to an appreciation of why our Waler horses are so important and advocated for so that we may still have them in the future.

(see A Romp Through History for the more detailed story!)

DRAUGHT:

All still in existence although rare.

Shires were originally called, by their studbook Association which started in 1868, English Cart Horses. The breeding developed from the Heavy Black Horse of the eastern counties in England. Shires were more agile than Clydes (which were bred to plough and steadily walk with farm machinery) and were far more widely used than people realise. They were greys, blacks, bays and browns. White markings were sometimes seen on legs and face. Many had little white. They had feather, from the knee and hock down.

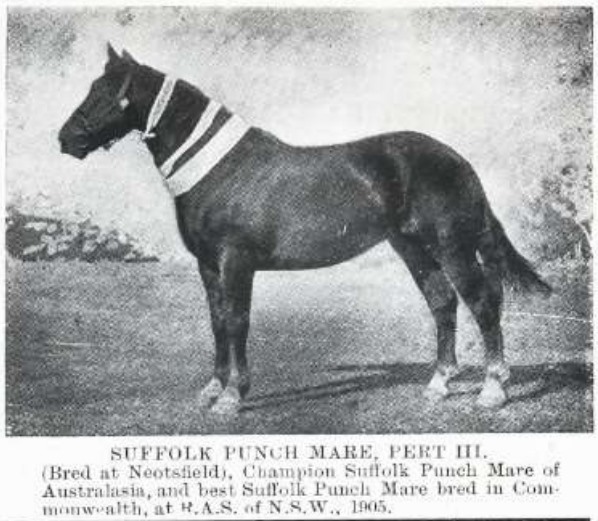

The Suffolk Punch traces back to a stallion, Crisp’s Horse of Ufford foaled 1768. The studbook was started in 1877 and became the first example of how a proper studbook and pedigrees were kept. Sturdy and nuggety, real chunks, and a clean legged draught. Stand square – good quarters and legs. All chesnut (spelled chestnut for other breeds).

Clydesdales were Scottish, the studbook Association started in 1877. Clydes rarely went to big runs for work, being too slow and lots of feather, they were more suited for smaller farms, but their crosses certainly went all over the place, these too were often just called Clydes. Clydes were roan, also black, brown and bay; white markings increased markedly as horse days ended. They had the most feather.

Percherons like Suffolks and Shires,were dual purpose, agricultural and a good road horse, sometimes called the Norman Percheron. First bred in the Le Perche area of Normandy, in France, from heavy farm horses and knight’s war-horses, crossed to Eastern and Spanish horses captured from the Saracens and during the Crusades. A robust, sturdy build. The neck was massive and upright. They had good natures, good bone, short cannons, and a good head not quite as large for their size as most draughts. Also a large eye for a draught.

COACHING AND HARNESS BREEDS:

The Norfolk Roadster (also called Norfolk Trotter) was a stylish carriage horse, sadly extinct as no studbook Association was ever formed, yet they existed in great numbers in their day. The Norfolk Roadster had high action that was also very fast, match races were common with them – one racing another, trotting, in lightweight sulkies from one town to the next.

The Cleveland Bay was originally called Chapman’s Travelling Packhorse (it was easier to pack than pull on the shoddy roads back then). Chapman meant a person who travelled about with goods loaded on a horse, a sort of carter or salesman. Solidly built, often long in the back. Very good, clean leg joints, plenty of bone and tendon. They have good action for dressage and can jump. The nose is convex (Roman) and long. A tremendous old breed.

Yorkshire Coach Horses or Coachers were created basically from a Cleveland Bay-Thoroughbred cross, then bred true to type. There were literally thousands at the peak of their times, Hyde Park a favorite place to show them off four-in-hand. A handsome, active harness horse of very good nature. As well as being a handsome coach horse, Coachers could canter and gallop well in harness – the Royal Mail, run to tight schedules and having to elude highwaymen, often galloped between towns. Heads long nosed and often a little Roman nosed, wide forehead. Good bone, hardy hooves.

The Lincolnshire Trotter (sometimes called Blacks, or Lincolnshire Blacks) was, like the Norfolk Roadster, a road horse for trap and carriage and as well for farm carts going to market. A little heavier than the Roadster, this breed were all true blacks with a star only or no white. The action was not showy like Roadsters, the knee action not as high but a working trot that could get along at a good rate.

CAPE HORSE (Boerperd)

We call it the Cape Horse, the historical name. South Africans also refer to Cape Horse in an historical context, but its proper name now is the Boerperd – Farm-horse in Afrikaans. The Boers realised their Cape Horse was disappearing, and in 1948 formed an Association to find any left and get them recorded. In the Boer war, the English had a terrible policy of attrition – they burned farms and killed all livestock they could find. Most of the Cape Horses were wiped out, literally thousands. The Boerperd Association finally found only six stations in the bush that still had pure Boerperds (Cape Horses).

PONIES:

Like the bigger horses, many ponies were brought out before having studbook societies formed, so are not recorded by their societies, although later imports are recorded. It’s in shipping lists and newspapers you find mention horses and their breed.

The Timor Pony The Timor is by far the most influential pony in the Waler’s make-up. Did ponies evolve there? Certainly taken there very early if not. Being isolated they developed into a good useful sort of breed. Ponies were a major trading commodity and sent all over in trade wind season. To China and India. Also Portugal had Timor for centuries so some went to Portugal and Spain. Probably got ponies from those places too, as well as neighbouring islands occasionally.

Java Ponies from the island of Java in Indonesia, went into the Cape Horse plus some came direct to Australia. Small, strong, tough little ponies similar to the Timor. Similar origins as the Timor, with some Spanish, Chinese, and Indian blood from the trading days of the Portugese, Chinese, Spanish and the Dutch East India Company and others in the region – looking at the old trading routes. Ghengis Kan’s raiders also left a lot of ponies on the east coast of Java when routed.

Sandalwood Ponies now called Sumba ponies (island name change) are a good, tough little pony like the Timor, some came out to Australia too, I’ve seen a record of a ship’s manifest with many Sandalwood Ponies listed, and there are doubtless more. Regarded as the best ponies of all that came here, always highly praised.

British Native Breeds (Dale, Dartmoor, Exmoor, Fell, Highland, New Forest, Welsh, Hobie, Galloway)

The main ones that came here and in great numbers were the Welsh. They were strong ponies of good bone and no founder bred in like now. Many were useful Welsh cobs, a galloway and sometimes horse-sized animal. Active, great bone, powerful. Only a very few of the other native ponies of Britain.

The history of England is one of invasion, many types and breeds came in over the centuries. Chariot ponies and war-horses made up the British horse population for centuries. The native ponies are ancient, being in England since the Ice Age. The Exmoor is the only one to have remained pure all this time – since the Ice Age – and is the pony that is most like the original Wild Pony. The brown colouring and mealy muzzles in some Walers may show Exmoor influence; there are Shires, Timors and Sandalwoods with this colour too.

By the end of the reign of James 1st The Great Horse was disappearing. This complaint was heard right up to the present as the famous heavy English horses and ponies got replaced by light breeds. Henry VIII wiped out breeds with his rule no entire male horse under 14.2 hands could live. Charles 1st made racing popular and it soon became the main sport and aim of breeding. The many breeds emanating in those times, heavy and light both absorbing much of the good old English blood, continued to the height of their perfection as studbooks were formed. This coincided with the colonisation of Australia.

The Hobie (also called the Hobby horse) an Irish breed, and the Galloway of Scotland. The English took over Scotland in the bloody days of “Butcher” Cumberland in 1745, and had 800 years of subjugating Ireland. “Galloway” now is the term for a height class, but it was a breed. Galloways were all dark – brown, dark bay and black, some had white markings. Hobies were many colours, often grey. Both breeds were popular in England and were directly descended from the pacing medieval palfrey, in turn descended from the ambling Spanish jennet. The important thing about these two breeds is that they naturally paced. They did not trot. Sometimes mentioned directly coming here but more arrived genetically as they were registered as Thoroughbreds.

BARB.

A horse of the Barbary coast, a breed that evolved there. Other equine species that evolved on the continent at the same time were the various zebra, asses and Quagga. The main countries the Barb was found – northern Africa – were Morocco, Tangiers, Tunisia, Egypt, Algiers, Libya, Tripoli and Fez.

Some were brought out directly to Australia for breeding remounts, for example Ben Boyd brought out six stallions in his ships The Seahorse and the Wanderer and released them on his properties on the Monaro for the India Trade. Shipping records give other imports, sometimes referred to as Barbs, sometimes as African, Barbaries, Morocco Horses, Berbers, Oriental and even Arabian – the place of embarkation however, is usually an indication of the breed.

As Arab peoples eventually invaded and occupied much of Northern Africa, home of the Berber people, Arab horses began to appear there and were crossed with Barbs. Pure forms of Barb were distinctly different and discerning horsemen of the time knew the difference. Arab horses of the time had been centuries in close captivity, pampered, and as now, had lost their ability to live unaided in the desert. They were still hardy regarding endurance, but they were too light, flat-footed, had low knee action and did not have the necessary frugality nor ability to exist in the wild unassisted nor on army fare.

The Barb however, had all the right assets. The British had colonised Tangiers and took many Barbs from there direct to England, they went into creating the Thoroughbred in great numbers. The French had many colonies there too.

The Barb is slim and elegant but with plenty of depth in the hindquarter, a long sloping croup to a low set tail, and has a long straight nose, occasionally Roman. The head is wide between eyes and nostrils. The under-neck muscle is often well developed but they can flex well at poll and crest. It is clean legged with hardy hooves. Frugal.

An active breed, it’s important in the founding of the Thoroughbred, Turkoman, Akhal-Teke, Andalusian and breeds descended from Spanish horses – which became most European breeds. Many countries such as Morocco, in modern times, have bred Arab into the Barb, thus destroying some lines of the breed. It’s believed to be in Algiers at present the Barb exists in its purest form, in greater numbers. Importantly, both Morocco and Algiers have National Studs to keep the breed going and pure.

At the time Australia was colonised, in 1788, the General Stud Book (Thoroughbreds) had not started, so the blood was close-up, as Thoroughbreds were just being developed. Many Thoroughbreds, as listed in Vol 1 of the GSB in 1791, were still pure Barbs. Barbs in Vol 1 outnumbered Arabs and Turks. “Thoroughbred” in fact, came to be the name of the English galloper breed – at the time it meant horses of eastern extraction suited to galloping races.

Arab: We got many from India in horse trade days. Traders that tok horses there almost always brought two or three Abrbs back, always stallions as the Arabian countries would not sell mares. There was a giant trade of Arab horses to India, principally for the British colonisers there but also for the wealthy Indian people. They were invariably pony sized. Tremendous bones. Long straight noses. Good doers. Used polo and racing, as well as army mounts. In turn used here to breed India horses and for polo and racing here, pony racing being a huge industry. Very good natured. Principally from Arabia (Iraq), Persia (Iran), Palestine and Syria.

THOROUGHBRED:

Weatherby published Volume I of the studbook in 1791, however it was only the beginning – the full Volume I was not complete until published again, a century later in 1891. The early book had, like many new studbooks, research and records going back some years before publication. Eastern blood was close-up, often still pure in the days of our settlement. The English racehorse was fast being developed by the beginning of the nineteenth century, and put to good mares, the eastern horses bred on successfully. The bulk of the horses used to create the Thoroughbred were English bred, with Roadster, Hackney, Galloway, Hobie, Clevelands and others all going into the mix.

Many TB’s were brought out early on to Australia and were important in establishing the Waler. Needless to say, in those days they were a lot tougher. They survived the long haul on ship from England and those taken to the bush survived happily there too. These days Thoroughbreds cannot exist in the same places. They were also, on the whole, a smaller horse. They have an average height gain of an inch every 25 years. There seems to be a misunderstanding with green horse people that Walers are descended from heavy Thoroughbreds, in fact they were descended from stayers which are generally the light types, and usually tall, with very good wind, big heart, big lungs and big nostrils, and a good length of stride. The heaviness in Walers comes from the draught breeds. They were all bred for distance races and jumps. Now bred only for sprints in Australia – a different animal altogether.