Shipping Horses to War

From Waler Data Base @FaceBook. Image: Loading horses onto the troopship HMAT Omrah at Pinkenba, Queensland, 1914. State Library Qld.

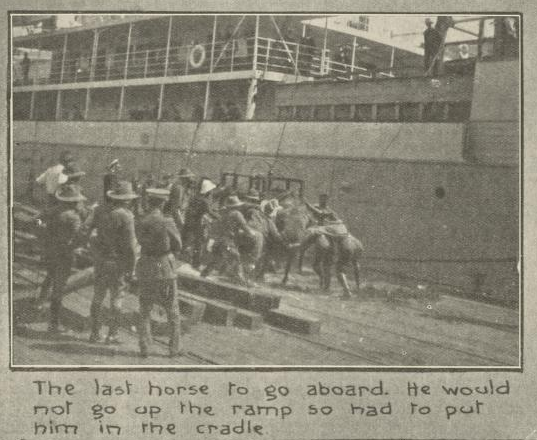

Ships were super quickly adapted with stalls and troop accommodation. Horses were loaded by ramp usually. Slings were carried to dispose of bodies, to load difficult horses, and to unload where there were no docking facilities. Crates for loading were the worst option of all (injuries, deaths).

Ships were requisitioned by the Navy for war transport of horses and troops. Horse export was part of our economy – most ship crews and horsemen were old hands at the game. Ships were super quickly adapted with stalls and troop accommodation. Horses were loaded by ramp usually. Slings were carried to dispose of bodies, to load difficult horses, and to unload where there were no docking facilities. Crates for loading were the worst option of all (injuries, deaths).

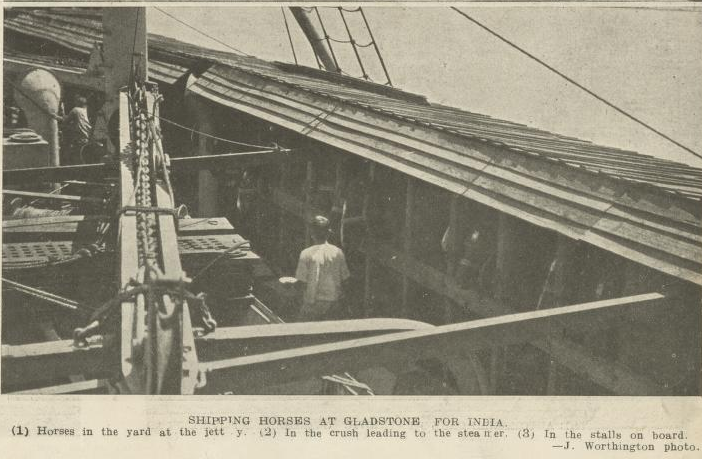

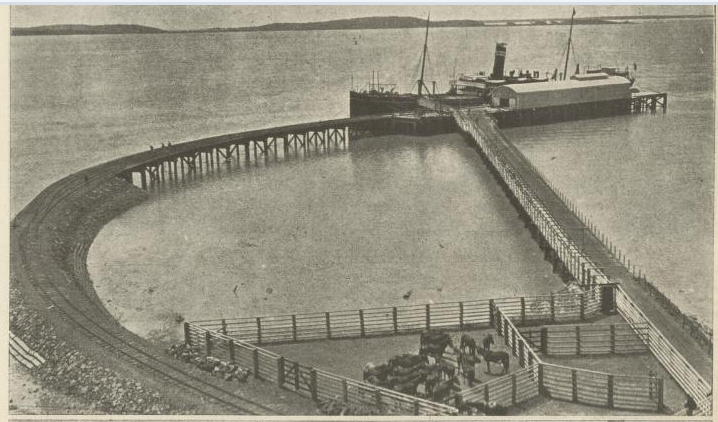

Images from Queenslander Pictorial, supplement to The Queenslander, 30 January, 1915.

On board ship.

Notice how some horses were kept among the men for some time, often the sick horses, or those moping in stalls. They did all they could to keep the horses in health, and in good mental health too.

The first convey of ships left in November 1914 from Albany, W.A. escorted by state-of-the-art Japanese warship Ibuki, who met up with them after escorting a convoy of NZ ships with troops and horses to Albany, to travel with us. We were fortunate that due to the horse trade, many ports were set up to receive and load horses.

Soldiers waiting to board the Omrah (ship) at the Pinkenba Wharf, Brisbane, 1914. State Library Qld.

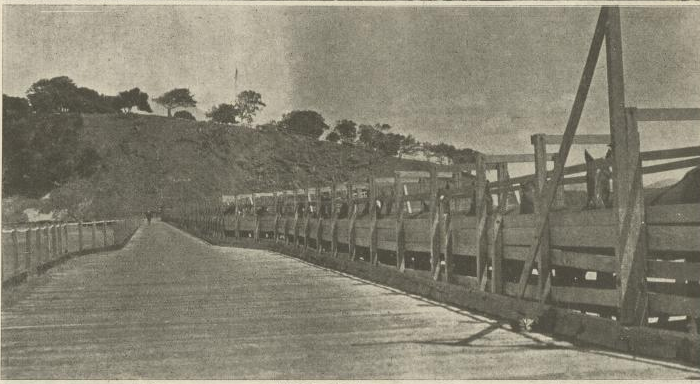

Pinkenba had railways run from country right to the wharf – purely for the horse trade. Likewise, big horse yards, water, feed storage. Rail to the ship. Loading ramps. Hence, when war came, the speed at which we could move horses, was all due to our existing horse trade.

Tons of fodder were stowed carefully to prevent moisture – and importantly – spontaneous combustion – in part of the hold that could be sealed off if a fire started, to deprive it of oxygen. Water was taken on board, but steam condensers – most ships carried two in case of breakdown – were the main form of getting water – making sea-water into fresh for the horses. Pressured hoses meant hosing down was efficient in the two to three times a day clean. Horses were taken out of their stalls – some stalls on deck, some below – while cleaning went on, at least twice a day, so they could have a walk. They were also massaged thoroughly to help their circulation. Feeding, cleaning, exercising, grooming and tending to problems made a long busy day.

Ventilation was critical, especially in hot areas. At least one vet always travelled with horses. Stalls were small, the horse stood all the way. This kept them safer in bad weather or big swells – in a roomy stall they’d be thrown about and killed. The stall sides, front and back supported them. Their feed bucket was on the front bar of their stall. Horses had to be taught to water and feed from a container before shipping, or they could not make the connection and would die, or start crib-biting. The bar on the front of the stall was usually painted with creosote if a horse started crib-biting from boredom, to prevent this vice.

Images: TSS Ceramic, Horses in Deck Stalls, 01 Jan 1915, Museums Victoria. There was always a loud noise of stomping hooves and joyful neighing at feed time, when they saw the men approaching with buckets; Horses and soldiers on board the troop transport ship HMAT Wiltshire, 1914 / W.A.S. Dunlop. National Library of Australia.

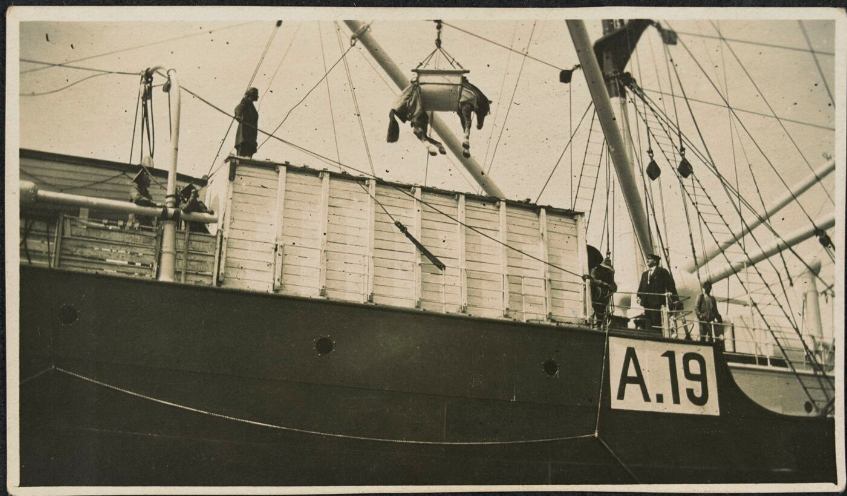

Slinging horses on board S.S. Karroo leaving Alexandria for Dardanelles. State Library Vic.

We sent over 6,000 horses to Gallipoli. Due to the terrain being more suitable for donkeys, most horses were shipped back to Egypt. Some of our horses went in there by submarine to avoid being seen at sea, hence expected by the enemy.

There are photos in archives of a father and son, soldiers, (name of Masters) on the S.S. Karroo. The father’s horse, Darby, was fussed over on the voyage, but fell ill, got poor, finally going down. They virtually lived with the horse trying to get it better. I don’t know if Darby survived the voyage or not. Hope so.

Our men were very fussy about caring for their horses en route to the war. They did a grand job. There were still illnesses and deaths among the horses, it is a fact of life, then they were thrown overboard. it was always upsetting for all, particularly the man who lost his horse. The percentage of loss was higher than with commercial horse shipping. All up, 44 convoys ferried 337,000 men and 27,000 horses to the European theatre. At risk of being bombed or torpedoed by submarines on the way. We also sent 81,000 horses to India during the war. Our Navy usually escorted our troop and horse ships; at times the Japanese Navy. During the war, there was a lot more transport on ships, small and large, of our horses, moving about war theatres.

Image: Troop ship (Bohemian) just pulled in along side the wharf, Alexandria, Egypt. State Library Vic. Horses with fly sheets on, over by the wall. They would have to be slung aboard, as no ramps, and ship too high for ramps anyway. Our horse ships for the trade had removable side sections to lower ramp angle – some could be loaded almost flat – no angle at all – which saved a lot of stress and danger.

Images: ‘Looking across wharf towards troop ship with crate holding a horse suspended over wharf, the number A19 on side of ship, Australian soldiers near wagon looking up at horse, an Australian soldier in left foreground. State Library Vic.; Page 27 of the Queenslander Pictorial, supplement to The Queenslander, 24 October, 1914. Shipping horses at Gladstone for India. The horses we sent to India for WW1 were mostly used for the war, Indian regiments, and British, taking them from India to Europe, the Middle East and where needed. Another port that had been set up for the horse trade. Hence making it fast and easy in time of war to load horses.