Feeding Horses in WW1

From Waler Data Base @ Facebook. Image: Horselines at Remount Camp, some of the horses are feeding from nose bags. Buildings can be seen in the background. Mena camp 1916. AWM

Feeding horses in WW1, for a recent request. An army marches on its stomach and horses have big tum tums! Especially Walers – a large gut area means they thrive on low quality feed. In war the feed is mostly low quality.

A massive undertaking in logistics. We were fortunate to have good officers.

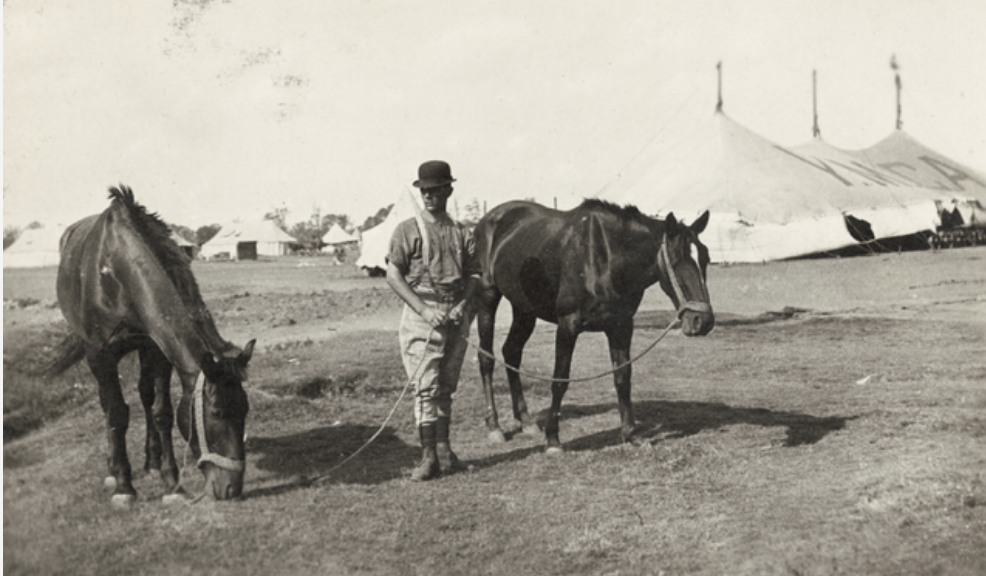

Image: Portrait of camp quartermaster. Broadmeadows, Melbourne, 28th August 1916. AWM

The quartermaster was often a Lieutenant in the WW1 era although sometimes a Sergeant; and at times other ranks. Importantly, he was chosen for his experience with horse regiments either as a career soldier, or long-term Light Horse volunteer; or a horseman in private life, or a farmer.

The Quartermaster General was critical. He had to be extremely capable. We were fortunate to have Sir John Cowan – British army. His duties covered Flanders to Mesopotamia ( now Iraq). As well as getting all the men needed from food to water, ammunition to blankets, uniforms to horse harness; he had to get horse feed and the right sort and amount.

He arranged horse feed (and all else) to be sent to the quartermasters of the various regiments for storage and distribution. Shipping, trains, wagons, whatever means necessary to get supplies to the men. He arranged buying the horses. Sending them to the war. Getting the men there too. All this of course done in Australia by various quartermaster ranks.

Cowan worked very closely with our Vet Corps, as they were used to source and distribute horse feed many times during the war, being on the ground. A wise liasion. For example Lieutenant Boreham with the Vet Corps was a veterinary surgeon as well having English and Boer war experience in the army, he worked closely with his quartermaster Sergeant Blair, who was a stock breeder, assisted by Sergeant Christie, an India trade man (horse trade).

Living off the land is mostly impossible in war – so buying feed wherever they went, stockpiling and transporting it was the usual way of getting fodder. The English had the luxury of a short albeit risky trip to France to ship feed to their army horses – they fed theirs well. For us it was too far – longer risk of ships being sunk, and of spontaneous combustion of horse feed. With most working men away we had a dire shortage of stock feed at home throughout the war, can’t find us shipping any apart from on the ships carrying horses (and as extra cargo, for use after arrival), and as cargo on ships carrying troops. Canada and the USA were the biggest shippers of horse feed to the war, they lost many ships doing it.

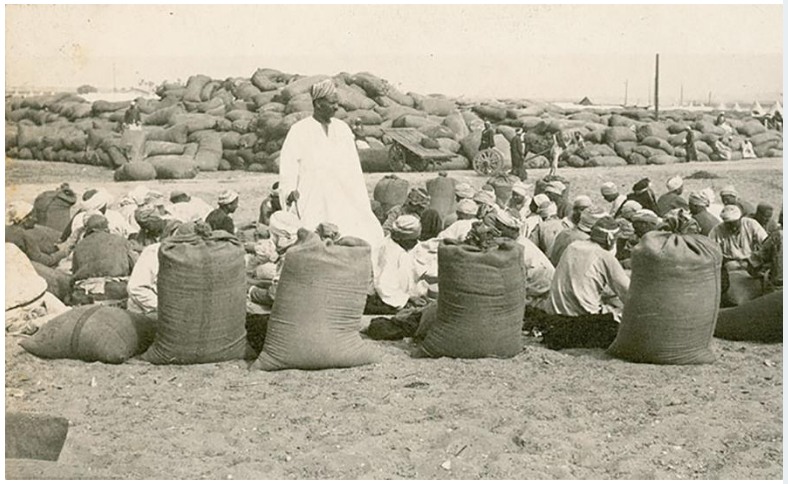

In the Middle East locals were paid to transport feed, grind grain and cut chaff for us. They took feed to the stockpiles, and from there to our men in the field. This freed our men for fighting. The local help was incredible.

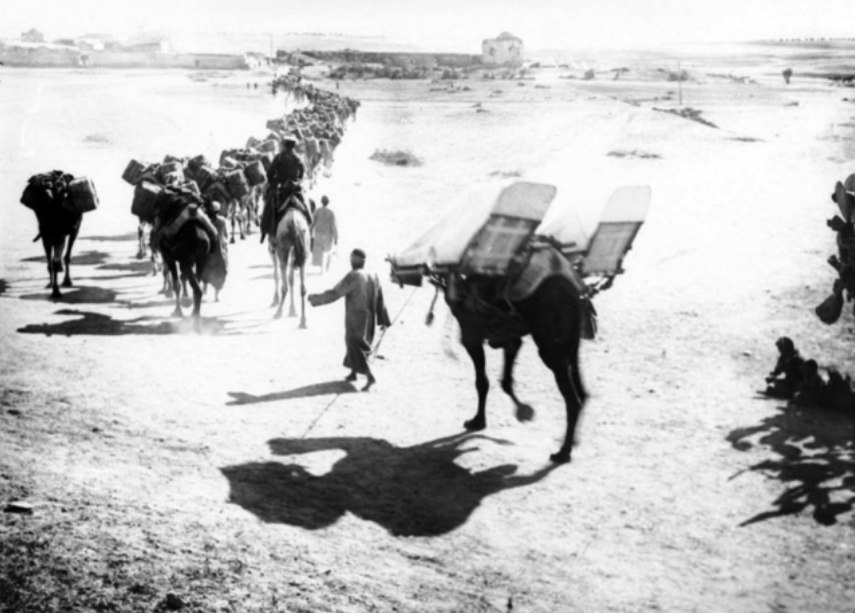

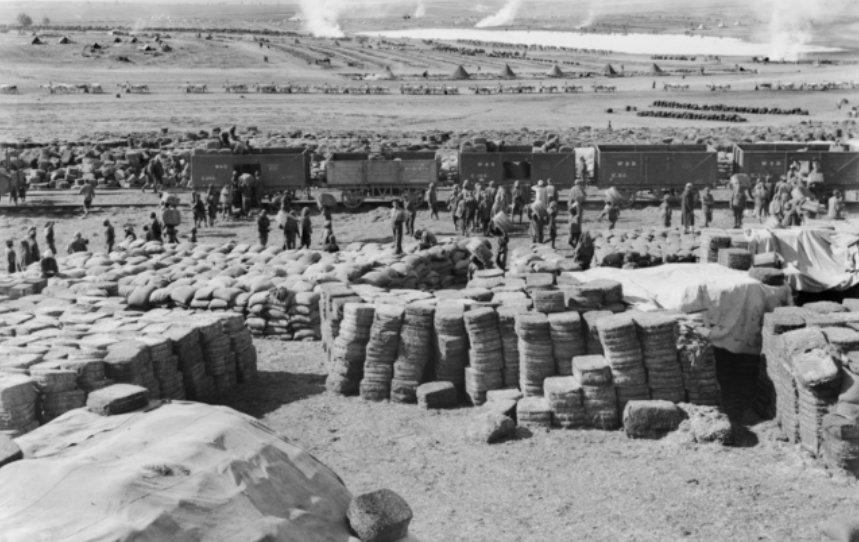

Images: Egyptians crushing barley for horse feed, Mena camp. 1914. From an album of Major Richard Casey. National Archives of Australia. There were about 10,000 horses in this camp to feed at any one time; Camels with Tibbin Sacks. Phillip Schuler photo AWM; A donkey pack train which carried horse fodder during the final operations. These animals were a very useful means of transport in the rough country north of Jerusalem and Ludd. September 1918. AWM locals walked hundreds of miles bringing our horses feed by donkey, mule and camel. They never rode, to save their animals.

In Europe our men mostly had to transport fodder and cut chaff themselves, thus taking valuable manpower from fighting. However often the Vet Corps and at times Field Ambulance men were tasked with locating, buying, stockpiling, cutting up and distributing fodder, to save other men for fighting. Horse soldiers are quick to find any feed for their beloved horse too – any chance for a pick of green, and a feed carried on the horse to get them through until supplies came along, transport always being slower than mobile horse units. The men’s own dinner was often shared with their horse.

The English too were good at finding horse feed. Despite having good feed shipped, it was never enough. Well done, men.

Images: ‘Australians cutting up horse fodder at Torpedo Farm, alongside the main road between Ypres and Poperinghe. Identified, foreground, left to right: 202 Private (Pte) Henry Herbert Goss, 40th Battalion; 10922 Driver (Dvr) H C Ryan, 22nd Australian Army Service Corps (AASC); 2267 Pte D R Robinson, 43rd Battalion; 1842 Pte A R Howard; 43rd Battalion; 6348 Pte G O Scott, 40th Battalion; 10822 Dvr C R Cobley, 22nd AASC; 10826 Dvr H S Creswell, 22nd AASC; 10882 Dvr Robert John Liddle, 22nd AASC; 10944 Corporal G G Taylor, 22nd AASC. Belgium: Flanders, West-Vlaanderen, Ypres. 30th September 1917.’ AWM; Australian artillery drivers filling up fodder nets for their horses at a camp between Montauban and Mametz. France: Picardie, Somme, Albert Combles Area. December 1916.’ AWM; ‘Fricourt, France. 1917-04. British Army soldiers gathering feed for their horses. (British Official Photograph C1670).’ AWM.

Fodder was carried by ship, horse-drawn wagon, cart, pack horse, camel, donkey, mule, and railway.

‘HORSE FEED / Typical feed for 15 hand horse / large tin holds one pound (450g) of / chaff. Small tin holds one pound (450g) / of oats. / Horses were fed at 8 a.m., 5 p.m. and / 8 p.m. At 6 a.m., 3 p.m. and 10 p.m. horses were fed 1 &1/2 pounds (680g) / of hay.’

From the collection of

8th/13th Victorian Mounted Rifles Regimental Collection. Victoria Collections.

The feed varied – whatever was available and in season. Hay of whatever grasses or grain crops were available. Hay from grain crops (straw, grain heads removed) chopped into chaff and sometimes crushed barley added in the Middle East. Chaff, with crushed oats when available, in Europe.

!['"Bersim [berseem] for the horses arriving into camp." Berseem is a green feed transported down the Nile River on feluccas, then transported by camels to a Remount Unit camp and fed to horses and mules. ' From an album of the 1st Australian Remount Unit in Egypt.](https://walerdatabase.online/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Bersim-for-horses-arriving-on-camels.jpg)

Images: ‘”Bersim [berseem] for the horses arriving into camp.” Berseem is a green feed transported down the Nile River on feluccas, then transported by camels to a Remount Unit camp and fed to horses and mules. ‘ From an album of the 1st Australian Remount Unit in Egypt; Tibbin stack. WW1. Philip Schuler photo.

Tibbin is what basic horse feed was called – meaning chaff but could be any sort of low quality chopped food, even barley sweepings and other grain husk waste such as from breweries, mills etc. Tibbin means low quality feed – still used as a term by sentimental Waler owners for plain chaff – Walers don’t need rich food – show a Waler an oat and you’ll be on the other end of the state at no time. And for yourself – if having a bit of bread instead of a proper meal, it’s tibbin for tea. Walers thrived on low quality feed so tibbin was fine, but a bit of crushed barley, bran and/or quality hay/chaff was prized in war of course.

AWM Images: A camel transport carrying tibbin (fodder). The cacolet camel in the rear serves the purpose of an ambulance for the wounded. Ottoman Empire: Palestine, Ramleh. WW1; The Australian Light Horse fodder dump at the railhead on the Philistine Plain. Ottoman Empire: Palestine, Deiran. March 1918. (This looks like compressed feed); Camel with a light load of Tibbin. Phillip Schuler photo.

A prime example of very poor logistics was Kitchener in the Boer War. He was hopeless – the horses died of over-riding, thirst and starvation – some 300,000. The disgust our men felt at the whole business there meant it was hard convincing people to join up for WW1. Thankfully logistics were far better with Australia being allotted officers of our own.

AWM Images: Feeding horses at military camp, Liverpool, Sydney. Any opportunity for a pick of green was taken, any time. The men knew their horse was their life and always looked for the main chance re feed; Horses of the 61st Battalion feeding during a route march near Westham camp in Dorset. United Kingdom: England, Dorset, Weymouth. May 1917; A horse of the Headquarters’ Staff of the 1st Anzac Corps feeding in the grounds of the Chateau at Querrieu, in France, in June, 1917. France: Picardie, Somme, Corbie Albert Area, Querrieu.

Watering has been covered in an earlier post, we had good portable canvas water troughs and piped water from wells, rivers or tanks; at times had it transported. Planning army routes and advances always had to take into account moving vast quantities of horse feed and sourcing water. Photos should help tell the story.