Farewell Old Friend

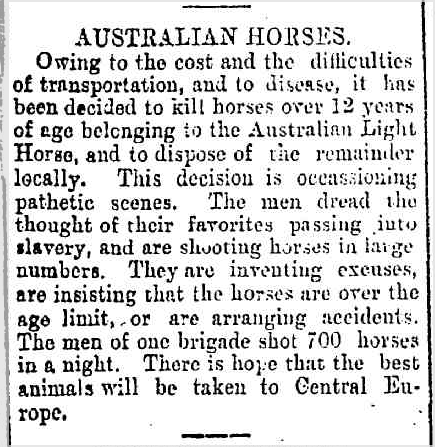

© Janet Lane, February 24, 2025. Image: Nhill Free Press, 4th December 1918

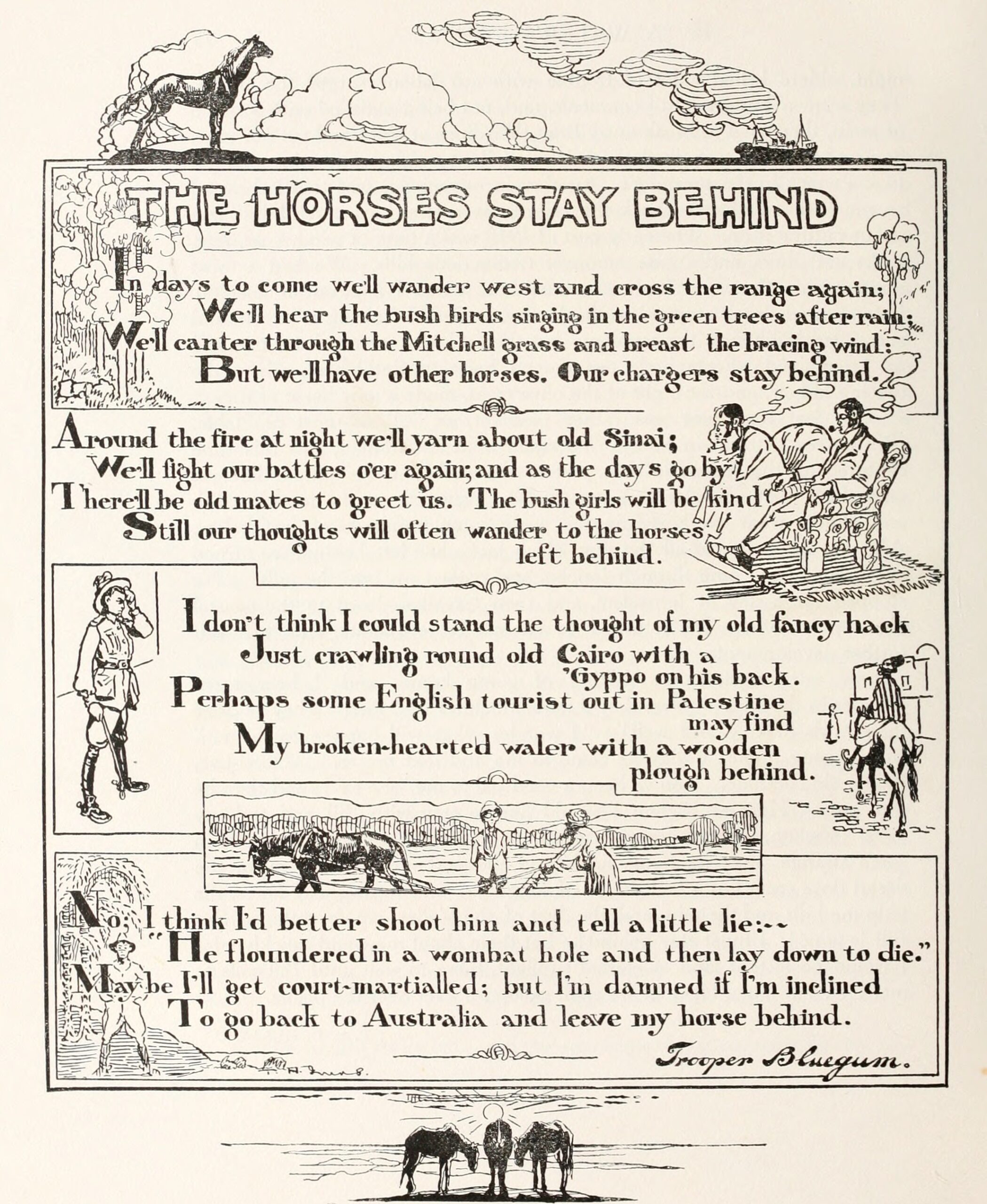

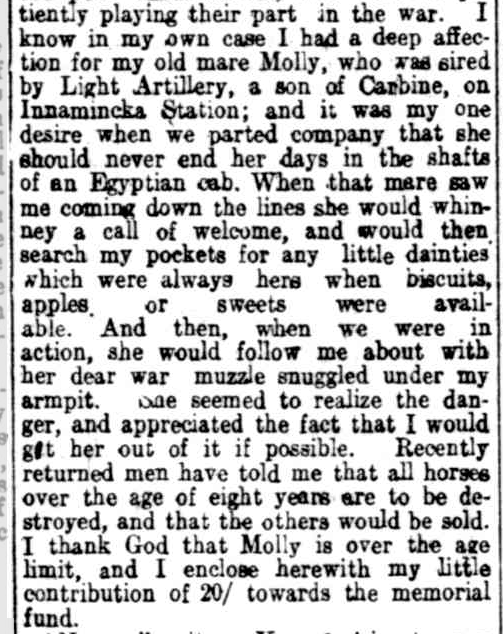

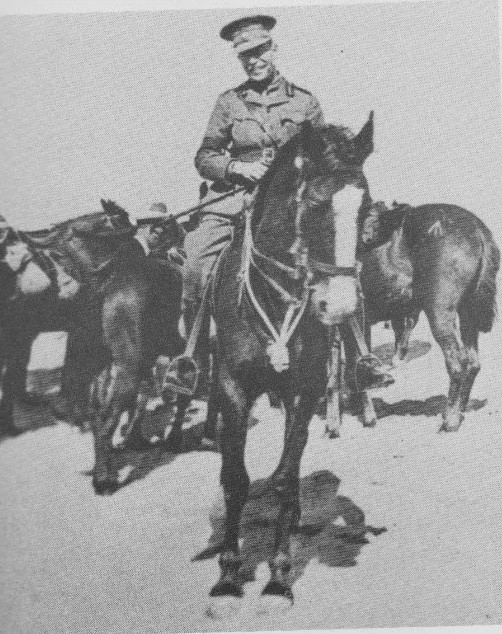

Images: The Horses Stay Behind, Trooper Bluegum, 1919 Maadi, Egypt. 1915. 2nd Lieutenant Oliver Hogue, Camp Commandant 2nd Australian Light Horse Brigade. WW1. AWM.

Trooper Bluegum was Oliver Hogue, a journalist. He died of pneumonia shortly after WW1 ended. He never got home.

What happened to the army horses after WW1? Yes, we all know, however there’s been a lot of discussion lately – were only the old and injured euthanised – as some coyly put it – by the magical euthanising fairy, or did the men shoot their own horse?

We need your help! If anyone recalls a Light Horseman, Artillery man, Transport driver, Ambulance driver or anyone from WW1 saying they had to shoot their own horse, please let us know. Diary entries are also a great resource.

Did the men shoot their horse on army orders or not? It hardly matters. It was an incredibly tragic time for them – the least they owed their beloved friend was a quick death.

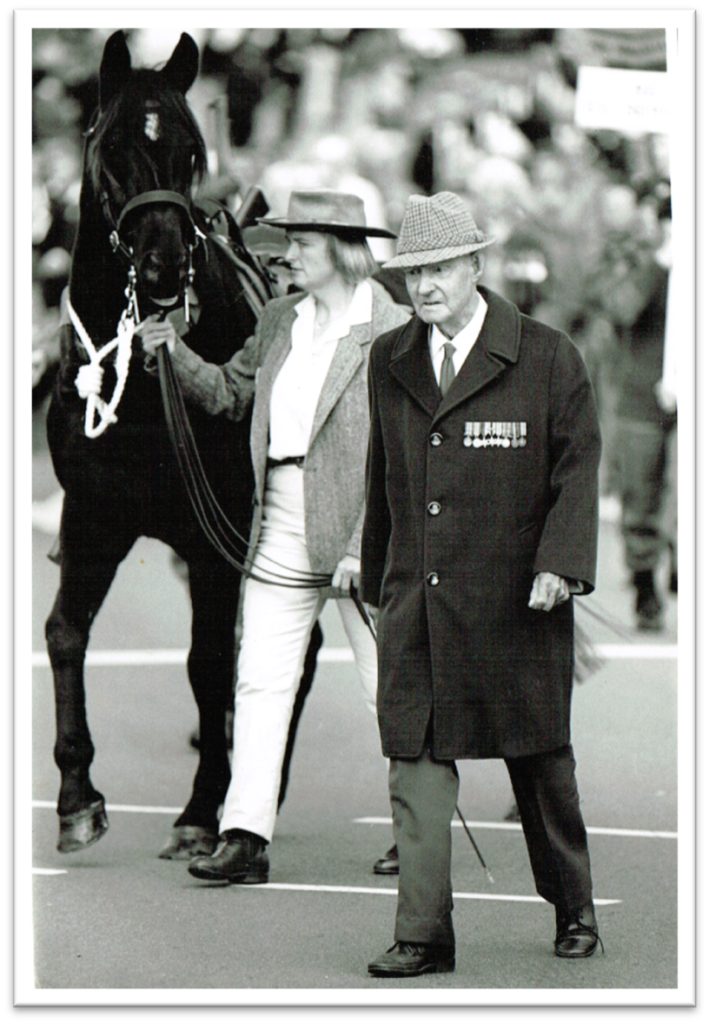

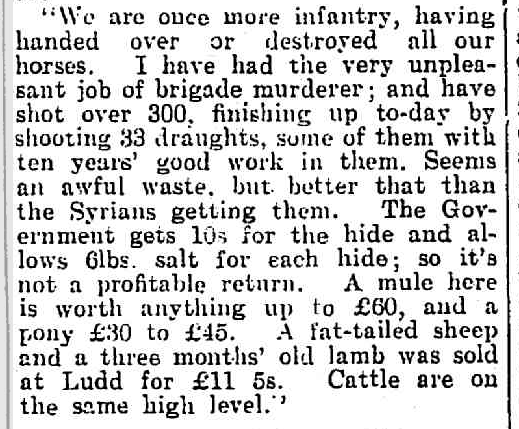

Image: Farmer & Settler, 1st December 1918

Twelve years old and up was aged. Goodness knows what was considered injured – but that was how to have your horse assessed for being shot (he’s very lame sir) when no-one’s looking. The issue of whether men took their horse out of sight and shot it without permission hardly matters frankly, but as there’ve been accusations lately this didn’t happen, if anyone knows it did, please share. It’s more likely they simply went on The Last Parade and did it with approval. Horribly, the men had to skin their horse afterwards and hack off their tail and mane, for the army to sell.

The countries the horses were in were war torn, occupied and poverty stricken – no place to leave or sell hundreds of thousands of big animals.

Surely for morale our government should have brought the horses home and kept them until they died of old age?

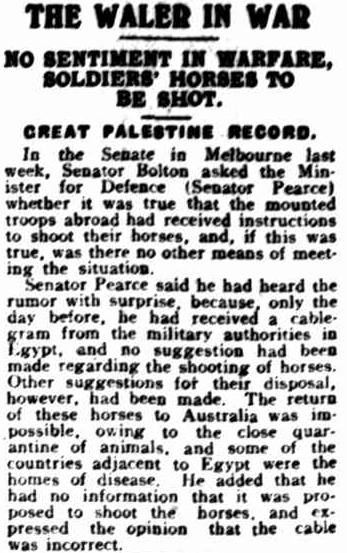

Image: Daily Telegraph, 5th August 1919

Quite a few were sold by auction in France to locals at very good prices – above meat prices. A few men who could afford it, took their horse to England, most being sold to country homes and several ended up great hunt horses. Some from the Middle East were left in Egypt with our men to fight an uprising against British occupation, a few months later they too were shot when the men were sent home. Some went to Indian regiments which had lost horses thus were eventually taken back to India. Their army, mostly Indians by ethnicity, looked after horses superbly.

Image: Ballarat Star, 22nd December 1919

Images: Muswellbrook Chronicle. 24th December 1918; Warwick Daily News, 21st October 1919

Few were sold locally in the Middle East and yes, with some tragic results but we never hear of those sold locally that were very well cared for such as Bill the Bastard – until a book was written about him.

At the end of WW1 700,000 horses were left in France and Belgium. 10,000 went back to the UK. 6,000 Australian horses were sold.

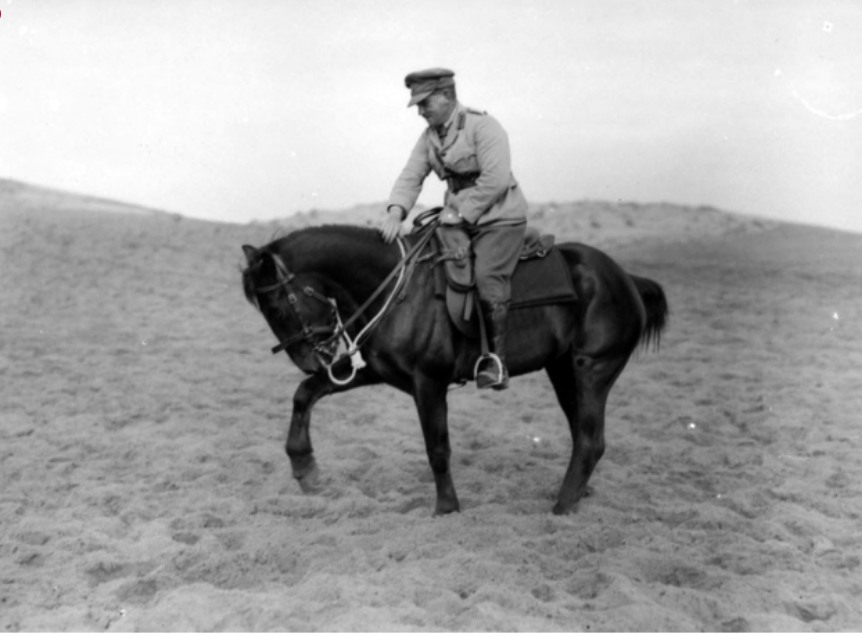

In 1919 a Memorial Water Trough for the war horses was decided on. Contributions for the cost were asked for – called “The Shilling Fund.” An outlet for men of South Australia to remember their horses either killed in war or killed at the end of the war. Shillings and the names of their beloved horses flowed in. Excess funds were donated to the Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. The Eternal Watering Trough is on the corner of East Terrace and Botanic Road in Adelaide.

Some donations from soldiers came in as horse names: Jibber, killed at Romani- the first donation received, of 5 shillings was for him, “in grateful memory.”

Tango, Two Step, Bobbie, Gambier (from southeast SA) raced in Cairo.

Banabooka, Colonel Tom Price’s horse, by Barbarossa out of a Pistol mare, bred in W.A., beat Gambier by a nose at Cairo in a race.

Doreen, killed under Major Seikmann near Ber-El-Abt.

Molly, originally ridden by Captain Norman Malcolm 9th LH, ridden by end of war by Major Parsons, being aged, although sound, she was shot. She was bred on Innamincka Station, by Light Artillery, a son of Carbine. Pigeon & Sugar (from Buckland Park, still going at end of war, fate unknown), Junk 20th AASC Australian Army Service Corps, Jingoe 20th AASC, Champion Judy, The two blacks: Taff, Warrior.

Darkie (in memory of Will’s Darlie), Captain, Tommy, Business, Turko, Bluebell, Retrieve. In memory of Jim’s two horses – bombed. Curley, Gentility, Domino, Kongorong, Brownie, Pally and Bill, Kind and Bronzewing, Jack (in memory of Jack), Members 18th Battery 15 shillings, Bobs (in memory of dear old Bobs), Billy (in memory of Billy who served faithfully for three and a half years in Egypt and France), Tim, Eager (9th LH), Dolly (Harry Woodcock for his faithful pony Dolly).

Bluejacket (in memory of Bluejacket by Polidore, by Panic who carried me 887 miles in seven consecutive days), Dolly (in memory of our Bill’s Dolly), Dolly, 5 shillings, Brownie (in memory of Brownie who carried her rider to safety after being shot, at the Jordan, March 1918), Nipper (9th LH), Peggy (in memory of Peggy).

Article is from The Register, Adelaide, Friday 17 March 1919 (including horse names); AWM Photo: Major Hudson, of the 1st Australian Light Horse Brigade, and his horse, Tango, trudging across the barren desert… Deiran, Palestine. 9th January 1918.

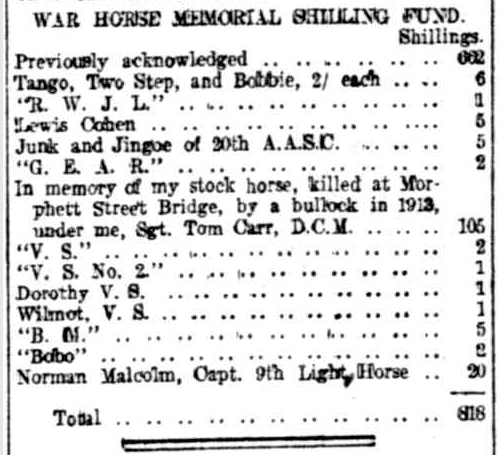

If you know of anyone who had to shoot their own horse, please let us know, and if possible, the name of their horse, if in Europe or the Middle East, and name of the soldier. We are actually not all that interested in the petty detail of whether men shot them with or without army orders, as frankly, same result and grief. It traumatized these men for the rest of their lives. Most could not talk of it until old age, then they broke down and cried, as many of us witnessed. I recall Ray Chatterton seeing Denny (Dardanelle), Jac’s Waler – suddenly and silently tears ran down his face, he managed to mutter what happened. He said “I’ve ridden many a mile on you old man” when he could talk again. He loved Denny, he hadn’t seen a Waler in decades.

Image: The Mercury (Hobart) newspaper

Ray Chatterton, aged 94, marching with Walers for the first time they marched in decades, in Hobart, 1990’s. Marching with stallion Dardanelle and his owner Jac.

Ray told us – Jac Kindblad, (then Pitcher), Terry Pitcher and Janet Lane), in person, that he shot his own horse after the war ended. He never got over it and said there was never anyone to talk to about it.

Ray flew from Melbourne to Hobart to attend the march specifically to see a Waler. He insisted on walking with Dardanelle the whole (very long) way, instead of riding in the vehicle provided for him.

Jac’s interest in Walers stems from her grandfather Roy Dickson, 3rd Light Horse. He enlisted in August 1914 and was in combat at Gallipoli by May 1915. Roy’s horses were Duke and Duchess.

Horace Flintcroft. Horace, 10th Light Horse. shot his own horse at the end of the war. He told this to Ros Sexton, as they became friends over her having Walers. He too said there was no-one he could talk to about it, and that he never got over it. This is recorded on ABC Conversations, interview about Walers with Ros Sexton and Janet Lane.

We have collected comments made by followers on our Facebook post 8 February 2025 asking for personal stories about what happened to the army horses after WW1.

Bless them all. It will be a good way to remember this trauma happened and do the men honor by remembering their horse and final act of courage. In future “discussion” with those who believe in the euthanizing fairy, or that all were rehomed, we can simply answer with a link to these memories, to save us getting upset.

This trauma does not relate only to WW1 of course. We know from personal anecdote that (with the transition to mechanisation) working horses were traded in for tractors, collected up and railed to Melbourne to be turned into fertilizer. As were those remaining in Light Horse Regiments when the army fully converted to armoured units in the late 1950s, with the Royal Australian Armoured Corps today carrying on the traditions of the Light Horse. Many, many, faithful service horses disposed of, traumatizing those who had the job of shooting them, in the case of the army horses, under the watchful eyes of the officers who had to remain until every horse was euthanized, no chance to save any of those brought in.

“My father Robert John Saunders fought in the Boer War on his own father’s steed, a roan that he sadly dispatched by a bullet to its forehead between the eyes so the … Boers did not get their hands on his beloved horse. This deed scarred his mind for the rest of his life. Something I witnessed the year I was 6 years old and he 66 of age…when he once again had to shoot yet another in our back yard. He sat with his head in his hands on our back steps sobbing raw hacking sounds with my mother’s arms around his shoulders.” Jacquelene Green

“I met a house painter on a property in 1960 who was in the Light Horse. From memory his name was Cyril Moore. He spoke of being given the choice by the company veterinary. Do you want me to do it, or, do you want to do it? I am not sure of the reason why Cyril’s horse was marked for its demise, whether it was age or some other reason, but he did choose to say his final farewell to his horse himself and was issued with a revolver to do so. He said he just led his horse away out of sight and said his final goodbye. He made no mention of having to skin it or cut the tail off.

There are many sources that state what happened to the still fit horses many of whom went to the Indian Cavalry. The French, I believe were left horses on the condition they weren’t killed for meat as the food situation post war was grim. The biggest hurdle to overcome regarding the return of Australian horses was being able to quarantine them and there was also no shortage of horses here but a huge shortage on the Continent. No horses were left in Egypt for obvious reasons but also they were too big for what was being used there, the demand basically was for pony sized beasts of burden that required less feed.” Raymond Fuller

“At the 2024 Anzac commemoration in Tallangatta a lovely lady (Susan) in her late 70s told us who were representing Sandy and all the Walers that her grandfather was in Palestine in the 6th Lighthorse. She said he loved his horses but that after having to shoot his own horse at war’s end, he never rode again! Susan said her pop worked tirelessly with his Clydies after the war but just could not bring himself to ride. Susan was brought up in the Riverina northwest of Albury and I think her pop rode to Seymour to join up.” Barry Stephan

“A story I read by a knowledgeable source, stated the Aussie and Kiwi soldiers swapped mounts so they didn’t have to destroy their mates. The British were forbidden to save their mounts, and they were sold to the locals and a life of unimaginable suffering. The Brookes Hospital was started as a means of saving those that remained as a response to this disgusting decision by the British army.” Chas Cooling (Ed response: Yes, the Brits sold most of theirs but their director of remounts, Birkbek, finally allowed the generals to have discretion, as hundreds of thousands were being sold, too many for those war-torn countries.)

Image: An Australian soldier, 244 Driver F W Stephenson, 2nd Australian Machine Gun Battalion, with a pack horse loaded with a machine gun at the Australian Pack Training School at Morbecque. This method of transport was being developed in anticipation of the subsequent operations in the Ypres salient. AWM

Comments below made by followers on our FB post 4 February 2025 featuring this photograph.

“Water-cooled Vickers machine gun. When I was a kid (1962) I met a bloke who had used one, he had won a prize for disassembling, cleaning and reassembling one in the fastest time. The prize was a tin of cigarettes, oval in cross-section and as thick as your finger. He didn’t smoke and had kept them since 1915.” Richard Windsor

“I’m still annoyed and angry at the way these horses were treated. My grandfather never talked about the war as such, but he was deeply troubled about the treatment of his horses.” Danny Nonme

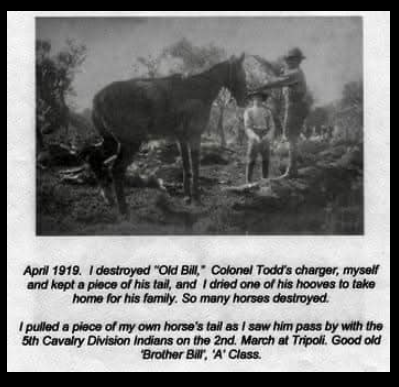

Merylin Stewart: “This photo is a Light Horseman and his beloved horse ‘Brother Bill’. If you knew what fate awaited the horses if they were sold (especially in the Middle East) I would 100% do the same. I believe it was a choice, I guess most men would prefer someone else do it but many had the kind of love that drew them towards doing it themselves…I have no doubt loving words were spoken at the time. I come from a town where the largest contingent was 10LH and I would say I’ve heard stories from different families that this was the case but the only proof I have is from the diary of a soldier.”

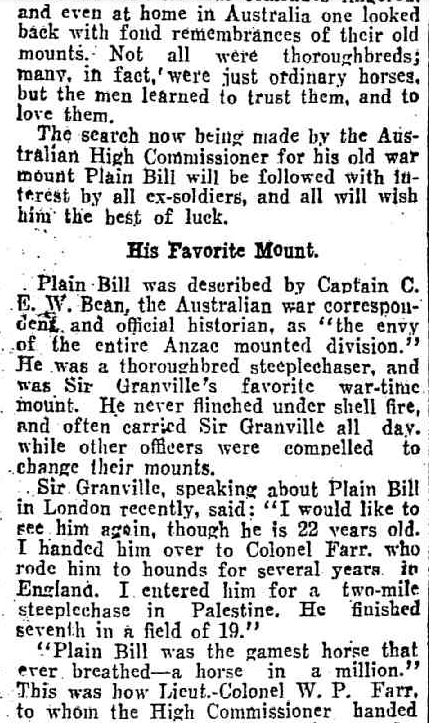

Image: Dead horses of the 3rd Light Horse Brigade. After the Armistice horses over the age of 12 years were destroyed. Tripoli, Lebanon, February 1919. AWM

There are very few, but some, photos of the piles of bodies in the Australian War Memorial, and of vets inspecting perfectly healthy horses, but saying they had to be shot. And the army made them skin them. The men couldn’t skin their own horse, so they did each other’s. That was the final bit of cruelty.

AWM Images: A small group of Australian soldiers walk between the dead bodies of horses lying in the desert. The horses have been shot prior to the return of troops to Australia. 1918; ‘”Dead horses”. From the collection of 1195 John William (Jack) Saunders, 3rd Light Horse Regiment. 1918; Soldiers of the 11th Australian Light Horse (11 ALH) stand amid the corpses of their horses as one of their fellow light-horsemen skins a horse after they were told they could not take their horses home. Cairo 1919.

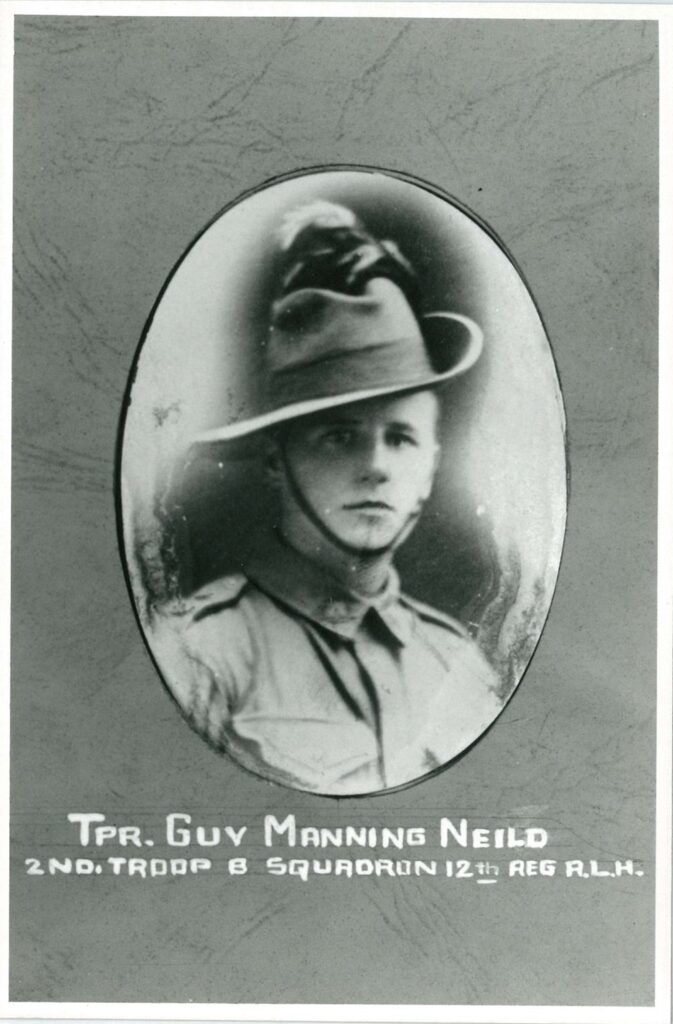

Image: Trooper Guy Nield, Northern Beaches Council Library photo

Article: Sydney Stock & Station Journal, 22 November 1918.

Australian and His Horse.

COMING HOME FROM PALESTINE

Mr. Joseph Nield, of Sydney Road, Manly, has addressed the following communication to Senator Pearce, Minister for Defence, Melbourne. This is a matter that should greatly interest the man on the land, as the major part of the Australian Mounted Divisions are made up of the men from the bush.

He writes: — “Now that the war in Palestine is virtually over, and the men under General Allenby have scored success after success in this brilliant campaign, it is well to remember (and good to think upon) that our Australian men and Australian horses have done so much, that we are justified in thinking that without them this hurricane campaign would not have been possible in the short time it has taken, if at all, it would not have been brought to such complete victory, without this combination of horse and man. The man to stand the extreme heat and dust and flies; the horse to travel long distances under these trying conditions, and with often only a cap full of feed to last him forty-eight hours, and a drink to start away with. It is such a feat of arms that will live for ages. And the tale of how the deliverers swept through the land will be told to generations yet unborn. At last, after five hundred years, the Great Crusade has succeeded in sweeping the terrible Turk and his desolating touch from those ‘holy fields.’ It has taken long years of sweat and sorrow in the wilderness to prepare for the entry into The Promised Land; but once the endurance of the Australians, and the stamina of the Australian-bred horse, has made that thing possible, which for hundreds of years has been talked of, and dreamt of by countless millions of men of high and low degree. I say it is doubtful if this galloping campaign could have been brought to such a speedy and complete success without that irresistible combination— the Australian and his horse.

The real Australian (always fond of his horse) has learnt to love his steed for the manner in which he has carried him on the long night stunts, on the wild charge across the sand-swept desert and over the rocky hill. It must be so, for the horse that has been a man’s constant companion for three years, is not easily forgotten or left behind, it would well nigh spoil some of the men’s home-coming, and well-nigh break their hearts to have to leave their beloved steeds in a land that is not congenial to them, and to a master who is not always kind. And this brings me to my question, viz. : Could not these men of the A.L.H., who wish be allowed to bring their horses back with them ; or have them brought back as occasion offers? This is my plea, and I ask for men to whom we owe much, and who would take this as the greatest reward. It may not be easy, but it will be as easy to return them as it was to send them over. It may be objected that there would be a danger of importing disease. That could be got over by a suitable and safe quarantine. It can be done, and I plead that it shall be done.

We owe these men — well, we owe them our lives and our liberty, and a fame and name that Australia could not have gained by a century of peace. They have showered Australia with a glory that shall shine down the long avenue of time. Who can repay? We haven’t done much for the men who were fighting first and last, and are fighting still. The returned man, the sick and wounded have been looked after and helped, and rightly so. But what of the man who has got no ‘Blighty?’ Who is fighting still, and fights in the end? Here is a chance to repay. There is nothing that would cheer the men so often, there is no favor they would value as much as the knowledge that when their work is done, they would be able to bring back the horse that has borne them so well — back to Australia to see him live and die in the horse’s Promised Land — dreaming the dreams of the days of yore among the luscious grasses of his native land. I know one, and there are many others, who would count it reward enough to bring back the horse that he took away, and has ridden ever since. I don’t know the intentions of the Government in this respect, but I do most earnestly hope that they will grant our brave men this privilege. I would say let each man keep his horse who wants to do so, and let the Government bring him back for him. If that can’t be done, let him have first refusal to buy him. If it is necessary let us start a fund for the purpose. I am willing to pay: and I’m sure there are many admirers of our Australian horse, and men who would be glad to do the same. It would be a graceful tribute to our brave sons.

The following reply over the signature of Senator G. F. Pearce has been addressed to Mr. Nield: — “Dear Sir, — I have received your letter of the 2nd instant, suggesting that members of the Australian Light Horse Brigades should be permitted to bring back their horses to Australia, and desire to inform you that the matter will receive consideration.” Yours, faithfully, (Signed) G. F. PEARCE.

Joseph’s son, Trooper Guy Manning Nield, had to shoot his horse Nobleman, and worse, was ordered to shoot 300 of his regiment’s horses, and the heavy horses of their transport and artillery section. Images from Sydney Stock & Station Journal, 23rd May 1919. After getting through the entire war, Guy came home and went onto the family farm to work. Less than a year later, in July 1920, he was found dead in a paddock, it was thought he may have fallen from a horse (although no horse was evident).

Meanwhile, for those who could afford it…

Images: Glen Innes Examiner 12th January 1928; General Ryrie on Plain Bill in Palestine on Armistice Day. Sunday Times, Sydney, July 1919. AWM

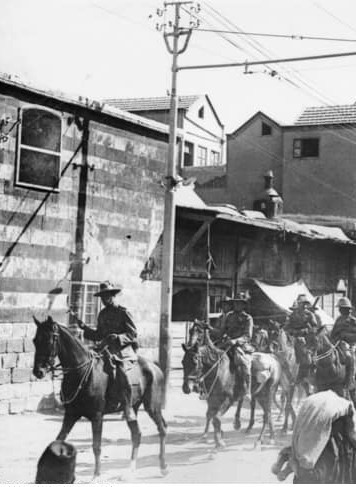

Despite saying the horses could not be brought back to England or Australia due to disease and a lack of ships, it appears several did get saved.

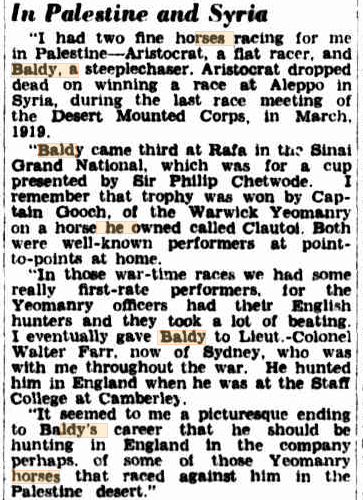

General Granville Ryrie’s mount Plain Bill, and Sir Harry Chauvel’s horse Baldy (aged) were taken from Aleppo, Syria to England by Lieutenant-Colonel Walter Percy Farr of the Australian army. He hunted Plain Bill for some time.

Baldy went to an officer at Aldershot who also hunted him.

Daily News (Perth), 17th January 1928 (article continues in images below)

Images: Brisbane Courier, 16th April, 1930; Chauvel on Baldy at the Rafa races, Chauvel Foundation website

Images: Chauvel riding Aristocrat through Damascus. AWM photo; Argus, 21st February 1939 (interview with Chauvel)